Inflation isn’t the real problem for the U.S. economy. The housing shortage is.

Government data recently underscored a truth that has become increasingly apparent over the last year: The primary force behind inflation in the United States is not a broad increase in prices across the board, but a significant national housing shortage.

Over the past year, inflation stood at 3.1%, a notable decrease from 2021 levels yet still high enough to warrant the Federal Reserve’s decision to maintain high interest rates. This recent inflation surge deviates from the pattern observed at the pandemic’s onset, primarily influenced by the increased cost associated with “shelter” as defined by the Consumer Price Index. This includes both actual rent paid and the estimated rent owner-occupied homes could command.

Except for housing, the inflation rate for most other prices has been minimal. The cost of goods has barely shifted, recording a mere 0.1% increase. Food inflation, despite being a significant concern post-pandemic, was under 3%. Other price categories even saw decreases, with household energy prices dropping by 2.4%, and vehicle prices falling slightly over 1%. Overall, excluding housing, the inflation rate was a modest 1.5%, a level where, under historical housing price growth rates, the Federal Reserve might have claimed victory.

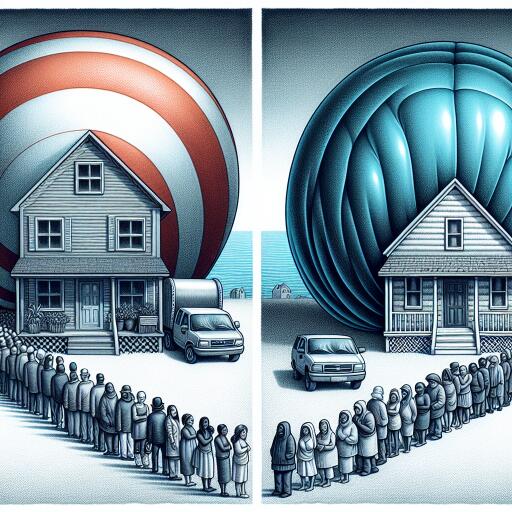

However, housing costs have skyrocketed at rates unprecedented in the last forty years, painting a starkly uneven picture of inflation’s impact. Homeowners and renters not subject to lease changes feel the effects of inflation differently from those grappling with soaring housing costs. For many homeowners, rising housing costs have paradoxically increased their wealth, adding over $2 trillion to their balance sheets since early 2022, despite the financial strain placed on numerous renters.

This trend disproportionately affects younger generations, with individuals under 35 facing significantly lower homeownership rates compared to retirees. Consequently, they are more susceptible to the adversities of climbing housing costs and less likely to benefit from the surge in housing wealth. In contrast, retirees, buoyed by increasing housing wealth and protective measures like Social Security and Medicare, generally see more favorable outcomes.

In response to housing-induced inflation, conventional tactics like Federal Reserve interest rate hikes, which have rapidly escalated mortgage rates, have proven ineffective in curbing housing prices. This is largely due to the housing market’s persistently low inventory, exacerbating affordability issues despite reduced buyer activity.

The ultimate solution lies in substantially increasing the supply of affordable housing. Estimates indicate a national deficit ranging between 1.5 million and 5.5 million units. Whiles some legislative efforts aimed at addressing this by funneling funds into programs such as the Housing Trust Fund and the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit have been initiated, substantial progress has been hindered by legislative stalls.

In lieu of sweeping federal legislation, a combination of state-led initiatives and incremental federal policies have begun to tackle the housing shortfall. Recent reforms introduced by the Biden administration aim to modestly increase housing supply through grants and funds dedicated to housing rehabilitation. Similarly, legislative actions in California seek to mitigate its severe housing deficit, although the urgency and scale of the crisis demand more aggressive and expansive strategies to alleviate and lower shelter costs.

While the Federal Reserve remains committed to combating inflation through stringent monetary policies, the resolution to our inflation predicament and the overarching economic stability hinges on a concerted effort to address the housing shortage crisis. A more aggressive legislative approach to increasing housing supply could dramatically change the current inflationary landscape, benefiting the economy at large.